The Zone of Interest

I still can’t get over “The Zone of Interest,” seven months ago. I saw Jonathan Glazer’s film about the Holocaust in May, and it just wouldn’t sit right with me I couldn’t put my finger on why. This is an event that has been explored in countless films Alain Resnais’ “Night and Fog,” Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List,” Roman Polanski’s “The Pianist” or the recently released “Occupied City.” All these movies demand you witness unbearable suffering under a brutal genocidal regime. But Glazer isn’t asking us to witness. He’s asking us to endure something much more uncanny than that. It’s a deeply unsettling work, immaculate in its discomfort of the viewer, which sanitizes like no other Holocaust movie before it.

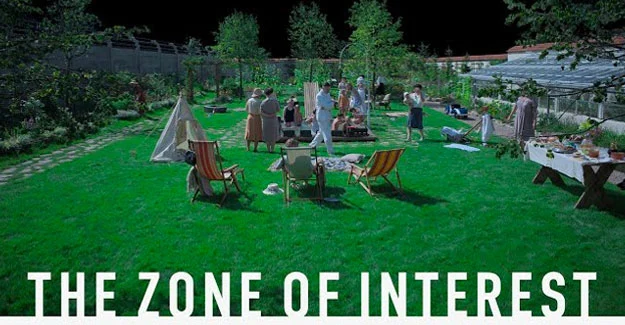

At worst someone could call it an exercise for Glazer to work strictly through atmosphere, telling this story from a German point of view Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) is the commandant at Auschwitz. The first time we see him he’s with his wife Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) and their kids, relaxing by the riverside somewhere near the camp; all around them are green fields and tall mountains. Then we’re shown their dream house, a tall concrete structure surrounded by an extravagant yard and even taller walls, on the other side is the camp itself. Except for one shot (of Rudolf through black smoking billowing in the background), we never actually see inside it. We’re asked to hear what it looks like instead. There have been two movies taking place simultaneously within “The Zone of Interest” one seen through sight, another through sound, as Glazer has explained but that tension is too obvious not to be powerful.

What hasn’t already been said about evil’s banality? As it turns out: The Hösses live next to an ongoing genocide and never comment on the daily screams or smell of death next door. So, yes, there’s a certain coldness to the film’s sentimentality. They raise their children as though everything is normal Rudolf tells them bedtime stories late into the night, takes them horseback riding, all that pastoral stuff so it becomes Hüller and Friedel’s burden (as actors) to chart a tricky course. How human can you make someone who is clearly inhuman? Friedel gives away nothing; his frigid posture speaks for itself. Hüller is slipperier. She plays her Hedwig like a rattlesnake with a blade for a tail. You see how Glazer frames them, and if they’re not up to the task well.

But this wouldn’t be new territory for Glazer. People hated “Birth” because of its ending and Nicole Kidman’s on-screen relationship with Cameron Bright, “Under the Skin,” while better received critically, walked a fine feminist line; all three movies pushed his audio-visual storytelling toward leaner, more angular compositions and a sense of sound that could unsettle. His debut was “Sexy Beast.”

In “The Zone of Interest,” with cinematographer Lukasz Zal, he furthers these two desires by often connecting interior spaces to outside sounds in a cause and effect manner: A train passes by bringing more Jewish people, then a package arrives at the house containing stockings presumably taken from the killed inhabitants of previous train. On Rudolf’s side of the wall people celebrate life (birthdays and social gatherings) while on the other side death takes place.

This close connection indicates how repulsively close-knit is Rudolf Hoss and his family’s relationship with destruction. They profit from an entire nation’s demise in ways too horrible even to mention: In one scene, one of Rudolf’s sons has a flashlight in bed. But he isn’t reading comics in the dark; he is sifting through his collection of golden teeth. In another scene, Hedwig receives a fur coat. She tries on the fine pelt, twisting her body to get every angle in the mirror. In one of the pockets she finds previous owner’s lipstick; in next scene she tries it on. Their comfortable nearness to murder is thrown into sharp relief when Hedwig’s mother comes over. At first her mother marvels at their “scenic” home. “You really have landed on your feet, my child,” she says to proud Hedwig. But once emanating sounds and smells reach Hedwig’s mother, her reaction shocks Hedwig.

In a film built upon dissonance, Höss’ persistent tidying up stands out prominently among other things that stand for ill-fated relationships between humans and non human entities such as nature or objects which are supposed to be neutral but end up being used for heinous purposes due to people’s wickedness towards each other.In this movie, every time Rudolf takes off his boots there is always a Jewish prisoner who cleans them, when soot from the camp touches riverbeds Rudolf’s children get scalding baths; whenever he cheats on his wife Rudolf washes his private parts in a slop sink before returning to her bedroom. Weeds are pulled, human ashes are used as fertilizer. Every misdeed by the Höss family works this way: hide behind another. Mica Levi’s ominous score can be deep and dirty during infrared scenes where a girl picks up food from mud, thus showing polishing on one hand and exposing on the other. The color white is used depending on this blurring fresh sheets, sleek suits or sterile office walls, even language itself with which everyone talks about death as if it were technicality or mechanics is meant to whiten over truth.If you keep talking circles around your crimes wouldn’t it be easier to continue performing them in straight line?

However specific it may seem at first glance though, Glazer’s film is just as much concerned with how history remembers disasters as when they happened themselves, so take for example that scene where after being moved from Auschwitz to Oranienburg Hedwig wants stay in dream house she made real while Rudolf speaks openly over phone to his wife about murder without euphemisms for first time ever before reacting grimly not even hearing most words because “It’s middle of night I need be bed” responds disturbingly then hangs up leaves office starts going down steps throwing up several times until he gets into dim lit hallway whereupon Editor Paul Watts cuts present day Auschwitz

It’s being cleaned so people can see the lost belongings now.

This sets up a contrast between two outcomes of cleaning. Throughout most of the movie, we see how cleaning works to destroy things. Here, she shows us that it also keeps them this way. Because our remembering what happened then and knowing what is happening now through propaganda, photographs, films and the Internet always involves both an unedited truth and one that has been altered. The fact that “The Zone of Interest” comes out at a time when countries are trying to rewrite history and cover up their crimes only makes Glazer’s pictures more powerful. Glazer doesn’t just mix up present with past or appearance with reality or life with death she does it so much you can’t ignore it.

For More Movies Visit Putlocker.