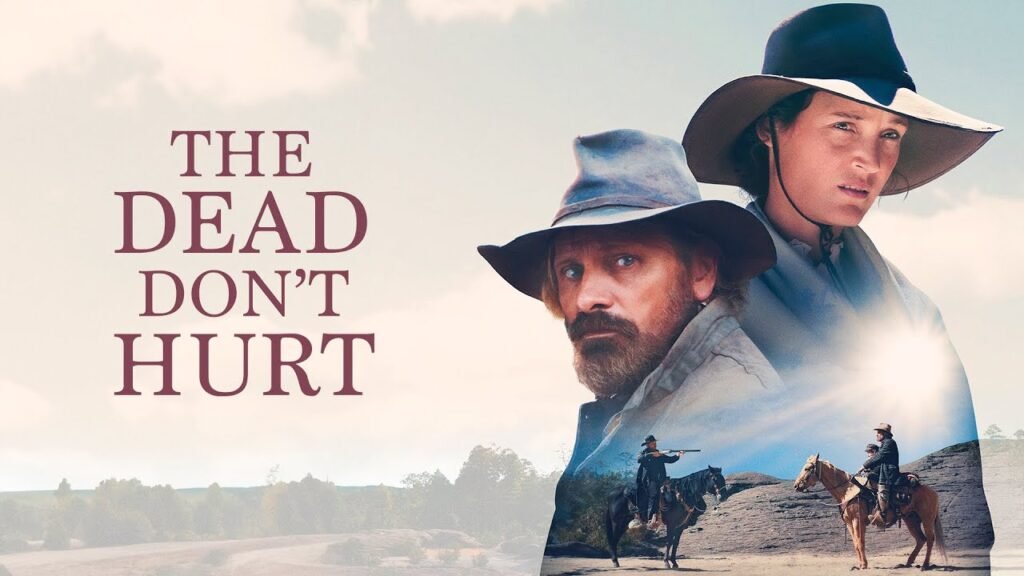

The Dead Don’t Hurt

A of my great great great grandfathers fought for the Union and survived the Battle of Antietam. After his infantry was killed he hid under a pile of bodies As a child I’d think about somebody doing that and then just going on to live a normal life, or what passed for normal in the late 1800s. I thought about him again watching Viggo Mortensen’s movie “The Dead Don’t Die,” which is a story mainly interested in the relationship between a man, a woman and a child, and the machinations among various people who live in the nearest small town but that also injects the kinds of big moments of suffering you’re used to seeing in more traditional action-oriented Westerns.

Written, directed and scored by Mortensen (in his second feature following the contemporary family drama “Falling”) and set before and during the US Civil War, “The Dead Don’t Kill” has standard genre elements but treats them as an entrance into something different than usual. There’s a sadistic psychopath who dresses all in black, some rich men who lord their power over this Southwestern town, a goodhearted soft spoken sheriff with an unremarkable past, his steely wife who keeps her own counsel but doesn’t take crap from anybody, their beautiful innocent son whom we’re gently prepared to believe could be murdered at any moment if certain dominoes fall into place elsewhere in this narrative equation.

But there are no stagecoach or train robberies hereabouts, no quick draws at high noon or other extended gunfights ending with thunderclaps of music and balls of fire rolling down Main Street. There is violence knife work early on that sets up one character’s backstory, whippings, beatings with fists; shootings at medium close range presented realistically and unsparingly but not often enough or at such length that we sense Mortensen getting off on the pain. The pace is what you’d call “slow” if you don’t like the movie, “deliberate” if you do.

Mortensen stars as Holger Olsen, a Danish immigrant who ends up as the sheriff of a small town in the American West. He lives in a tiny cabin in a canyon. I’m not going to tell you exactly where the movie starts or stops because it’s nonlinear and accounting for things in terms of a linear timeline would give you an inaccurate sense of the picture and spoil some surprises, but suffice to say that eventually he goes to San Francisco and meets this French Canadian flower seller named Vivienne Le Coudy (Vicky Krieps) and brings her back to his cabin, where she overcomes her disappointment at his bare bones lifestyle and tries to build a life for them and the son they will eventually raise together.

Meanwhile meanwhile meanwhile, though also now plus both before after later on still then soon my God this movie drives me crazy! we keep revisiting that aforementioned town controlled by Alfred Jeffries (Garret Dillahunt), with Weston Jeffries (Solly McLeod) acting as his muscle when necessary, plus Mayor Rudolph Schiller (Danny Huston), who controls most of the local real estate plus the bank. There’s tension surrounding ownership of a saloon staffed/tended by an eloquent barkeep manager named Alan Kendall (W Earl Brown). A shootout depicted early on passes control of said saloon into the hands of the Jeffries family. Vivienne winds up working there. Weston takes umbrage at being told he can’t have her.

I said before that this isn’t a linear film, and I say it again here because there’s no cause and effect in it even though there may be one somewhere. It takes some time to realize how the story is being told. Mortensen’s script works against our movie brains’ conventional thinking on purpose. He begins near the end of his tale and moves from present tense to various points in the past as required. The shifts in time aren’t plot- or theme-related; they’re intuitive, like brushstrokes.

There are also flashbacks to Vivienne’s childhood, when she lost her father fighting the English a trauma that triggers a dream or hallucination of a knight in armor galloping through a forest. This image connects with the middle of the film, when Holger rashly enlists in the Union army to fight slavery and collect a promised enlistment fee, leaving Vivienne alone in that tiny house in the canyon. This might seem casually cruel to people watching now, but things like this happened all the time then, and tend to be summed up in family histories by saying “Then he went off to fight in the war and came home a year later.”

The writing and acting for all of these characters is intelligent and measured. You get a strong sense of fullness whenever you spend time with somebody who has had a long life offsetting other characters who have only been granted brief moments carefully chosen for maximum effect: Brown’s character is a little too pleased with his own eloquence but sometimes seems ashamed after he verbally steamrolls people, a judge played by Ray McKinnon presides over the trial of an innocent citizen accused of an unspeakable crime; he behaves as if God guides his gavel (which doubles as pistol butt); and veteran character actor John Getz (of “Blood Simple” and “The Fly”) plays Reverend Haygood, whose community role requires him to oversee an execution even if it’s unwarranted. (Brown and McKinnon were on the HBO Western “Deadwood,” a go-to casting resource for this kind of project; it’s a kick to see them play very different characters from ones they’ve done in the past.)

None of these characters reveal themselves as expected. Holger seems at first like a Clint Eastwood style strong silent he man archetype, but he’s indecisive, sensitive, and book learned. He frequently reads or writes in parchment-bound books or journals. His tenderness toward Little Vincent (Atlas Green), his son with Vivienne, is unusual in movies that spend much time considering manhood or heroic codes, so is the physical warmth he shows the boy. His relationship to the western hero code summed up as “doing what a man’s gotta do” is more complicated than most such relationships. Olsen makes many decisions that would result in negative comments on audience preview cards from focus group screenings (it’s hard to imagine Mortensen doing one) because they are not things that typical western action heroes do they’re more like what real people with complex psychologies might do, and regret later.

Krieps, who broke out in “Phantom Thread,” is really the star of this movie, though it begins and ends with Mortensen’s character riding off on a long journey.

She is the only one of the characters who ever gets flashbacks or dreams. She walks a very fine line with her character in that she makes her seem self-assured, tough and self respecting without ever making her look anachronistically “feminist,” in the forced, artificial way so many period pieces feel compelled to write female characters from earlier times. Krieps is an unshowy but deep film star, of a type we haven’t seen much since actresses like Liv Ullmann and Ingrid Bergman. She reaches out through the screen and connects with you. You can actually feel hope draining out of Vivienne when she keeps a stiff upper lip through terrible things that are happening to her for no good reason except rotten luck. But you can also feel the resolve when she decides to make the best of it anyway, and the thrill that goes through her when somebody treats her as though she has value as a person.

There aren’t very many movies like this, maybe three or four (like Sam Peckinpah’s “The Ballad of Cable Hogue” or the Charlton Heston movie “Will Penny”, or “Deadwood”, or Jan Troell’s 1970s movie “The Emigrants”) but when one comes along it stands out: among other reasons because it doesn’t go to any of what have become the predicable, ritualized high points in stories set within these conventions and there are half a dozen moments here which could be those high points and instead spends its energy on places where two people draw nearer together in understanding themselves and each other better, without either party having anything like even a 20th century mindset superimposed upon them. Because none of this material panders to us or our time because nobody does anything here just because people do such things now it’s all slightly at a remove from us throughout, which means it seems unusually real. Yes, some things about being human are universal and don’t change. But people have always known themselves and each other very differently at different points in time, and this is a movie that knows that.

What I mean to say is that the movie has a genuine, cinematic instinct both for when to linger on a moment and when to cut around it, or allude to it as something that occurred offscreen: many of the longer sequences are merely extended conversations between the film’s two romantic leads (whose banter is sharp but who derive most of their chemistry from looking resentfully or longingly or gratefully or disappointedly at one another). You almost never get to see material of this sort play out at length in a film set in the American West. Or any kind of film, really.

Mortensen is 65 years old now (three years older than Eastwood was even in “Unforgiven”), and on top of everything else Westerns are even more out-of-favor with film industry power brokers today than they were back when Kevin Costner made “Open Range”; so long story short I think we can probably rule out the possibility of him making any more movies like this one. But if he does he may yet go down as one of the great Western directors.

For More Movies Visit Putlocker.