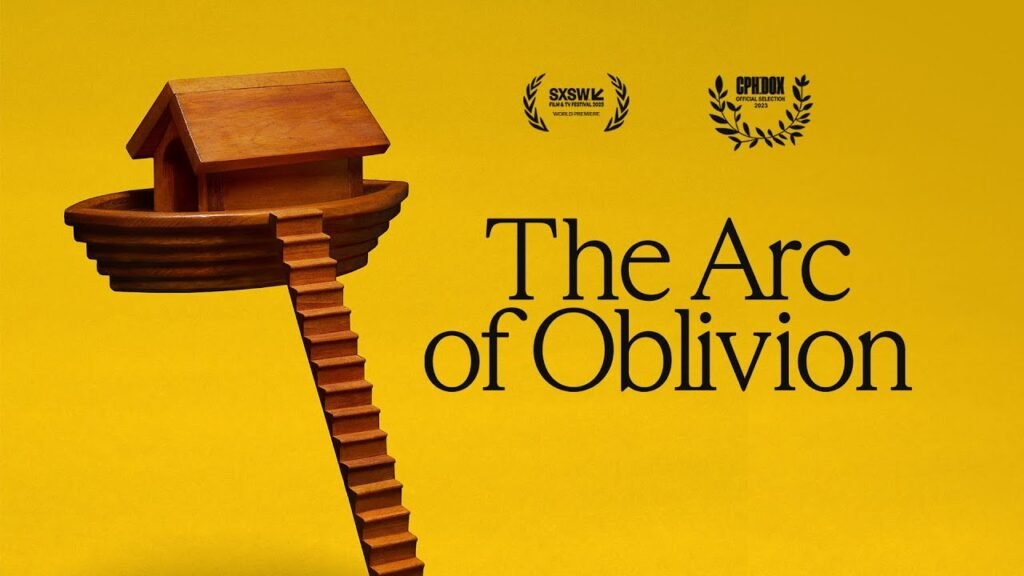

The Arc of Oblivion

The movie is called “The Arc of Oblivion” and it concerns many things, one of which is the futility of its own creation. Ian Cheney, who wrote and directed and narrates this film, is a kind of hoarder mostly of hard drives full of photographs, video and audio files from his life that range in significance from obviously important to what might be called “curiosities” (for example, a snapshot of a man identified as “the world’s greatest barber” cutting another man’s hair, framed). He has also collected other people’s material, or it has come into his possession: A slide box full of photos kept for decades by his father on which he had written “The Ark.” When he opens it at last it contains one shot of his mother sitting on a rock and two shots of red wine glasses in front of a pumpkin; there is no way to know why it was valuable enough to keep.

The title is punning at several levels. The movie’s structure involves Cheney building an actual ark (small “k”) like those in the Old Testament or the Epic of Gilgamesh on family property in the woods in Maine to contain all this stuff. Making that vessel is a way to impose some form limits or boundaries on top of a mountainous heap of junk and data he has humped down through the years as well as a self deprecatingly funny slap against impermanence itself (as if putting all your stuff in a boat on dry land weren’t going to preserve anything!).

It’s also somewhat arbitrary and cool (maybe gimmicky Cheney knows this) limit setting with respect to the 98-minute feature you are watching. Given what it’s about, “The Arc of Oblivion” could just as easily have lasted nine hours or nine days. And yes, the c in arc lets us know that this is all ultimately pointless, though we might dream otherwise. Or as Bruce Springsteen sang in “Atlantic City,” “Everything dies, baby, that’s a fact But maybe everything that dies someday comes back.”

The famed German thinker Werner Herzog may not have had anything to do with “Arc of Oblivion” aside from executive producing it, but his presence is felt throughout in Cheney’s narration, which immediately vanishes up its own navel and manages to be entertaining and funny anyway because it’s both self-mocking and sincere; in a buried (like, deep under the creative soil) nod to Herzog’s own filmography, which is filled with stories about men who went on a mad quest to put up a monument to their own existence only to discover that it’s an exercise in futility.

It would be interesting to show this movie as part of a triple feature with Herzog’s “Fitzcarraldo,” about a rubber baron hell-bent on getting a steamship over a hill in the Peruvian jungle, and “The Burden of Dreams,” Les Blank’s documentary about the making of “Fitzcarraldo.” What Cheney is doing here is the self effacing 21st century American bourgeois artist equivalent of what a Herzog hero would do when confronted with the fact that he and everyone he knows or has ever heard of will eventually die, and that the civilization they were part of will fade until only fossil records remain.

It’s an exciting picture. There’s so much happening in it that you can’t take it all in on one viewing mainly because Cheney and his collaborators have kept things loose and light, adopting a “no big deal” attitude. You could easily mistake it for an intellectualized form of escapism, like listening to one long National Public Radio story about an eccentric. I’m glad I’m writing this almost a year after seeing it for the first time during its 2023 South by Southwest film festival premiere. The fossil records are showing now. It’s one for the ages by which I mean that in several more decades almost nobody will remember it, or the filmmaker, or me, although I wouldn’t rule out the possibility of my thinking about it on my deathbed.

For More Movies Visit Putlocker.