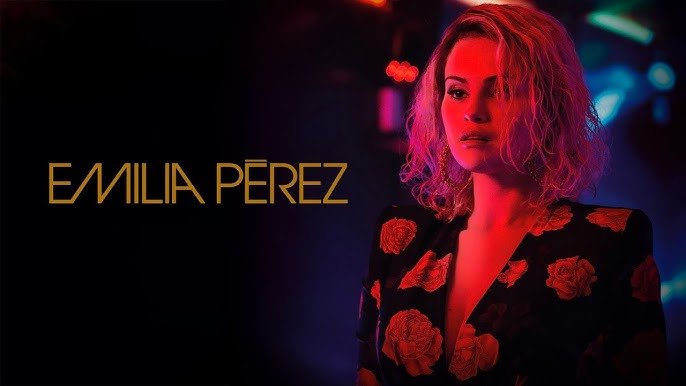

Emilia Perez

Which film director do you think I am if you were told that in cannes an original musical is shown about a tough and heartless drug lord who wants to change his gender? May be Pedro Almodóvar or John Cameron Mitchell?

Jacques Audiard won the Palme d’Or in 2015 for “Dheepan,” but he’s not exactly a name known for sticking to one genre or developing a signature. He made the prison movie “A Prophet,” the western “The Sisters Brothers” and the 21st-century romantic roundelay “Paris, 13th District.” Even so, it comes as something of a shock when, at the beginning of “Rita Moreno,” Zoe Saldana starts singing about her murder trial defense client. We don’t usually see songs there or anywhere else in an Audiard film. (The music is by Clément Ducol and the mononymous singer Camille.)

So there must be some value in taking notice of a filmmaker willing to take this many left turns. For this one, Mr. Audiard has gone all-in on a widescreen, mainly Spanish language production that is just going for broke. There’s a number about vaginoplasty, soon after comes another song as Rita tries to persuade Mark Ivanir’s doctor character in Tel Aviv to travel to Mexico to meet her client. The film then follows the friendship that forms between Rita and Emilia Pérez, a former drug kingpin played by Karla Sofía Gascón (four years after they reconnect in London, Gascón could well win this festival’s best-actress prize for her performance as Emilia). Emilia wants to make amends with her wife (Selena Gomez) and children having lived with them for years under Swiss snow globe circumstances, she doesn’t know who they are either and it’s during these twisty family scenes, as Emilia plays aunt to her own kids, that the film most closely resembles Almodóvar.

But then if it were an actual Almodóvar movie, it would be far less surprising. With Mr. Audiard at the helm, it looks like a big swing a movie willing to risk making itself look ridiculous in service of its opera house ambitions. If “Rita Moreno” is a folly, it’s one that, for this director, lacks personality; that becomes clear in the second half of the film when its style has settled and he has to get on with storytelling.

For example, three years ago at Cannes there was “Annette,” Leos Carax’s collaboration with Sparks now there was an opera that went big and weird. And two days ago we had “Megalopolis” now there was a folly. For all its clunkiness or inertness or whatever else might be wrong with it, “Megalopolis” feels like a movie that poured out of Francis Ford Coppola’s mind and onto the screen; it teems with his private preoccupations (historical/political/literary/cinematic). “Rita Moreno” may have more polish and pizzazz than anything here in competition except maybe Wes Anderson’s “The French Dispatch,” but this film seems instead like something Audiard worked on as a dare rather than an obsession.

Also, “Three Kilometers to the End of the World” is a good solid drama with an annoying machine made quality to it. Directed by Emanuel Parvu (an actor whose work includes 2022’s “Miracle”), this film follows in the tradition of Romanian New Wave movies over the past two decades by being about a slow-burning crisis. One night, Adi (Ciprian Chiujdea), a 17 year old boy, is violently attacked, but efforts to apprehend the assailants run into various investigative and bureaucratic snags. Then it comes out that Adi was beaten because he’s gay which suddenly changes the priorities of the homophobic residents of his town. Who cares about bringing violent thugs to justice when there’s horror a gay person who needs dealing with?

Compared with films by Cristian Mungiu (“R.M.N.”), Corneliu Porumboiu (“Police, Adjective”) or Cristi Puiu (“The Death of Mr. Lazarescu”), “Three Kilometers” seems both less demanding from a formal point of view and insufficiently thorny. I have no doubt that homophobia is an issue in some parts of rural Romania, but there are few real ambiguities for viewers to grapple with here; nobody watching this movie is rooting for the priest who wants essentially to exorcise Adi and posits at one point that his treatment methods are as sound as medical science Clearly, Adi has been wronged and deserves justice. Parvu’s film preaches to the choir.

Jia Zhangke’s “Caught by the Tides” is easily this year’s competition entry that has proved hardest so far for me to write about, though I can’t claim I know what I think after only one viewing. Much of it consists of footage Jia has shot over more than two decades since 2001; often set in (or near) the northern city of Datong, it contains a middle section aspect ratios and image quality vary with the passage of time that returns to the Yangtze River material he apparently shot for “Still Life” (2006), which dealt with consequences of the Three Gorges Dam’s creation.

There are many callbacks to Jia’s previous work in “Caught by the Tides,” and even longtime fans may struggle to catch them all. The film effectively updates the conceit of his breakthrough film “Platform” (2000), which viewed China’s cultural change through one particular character’s eyes, with songs and dances. Qiaoqiao is largely silent throughout this movie (and sometimes Tati like in her interactions with a robot), she is played by Jia’s longtime leading lady (and spouse) Zhao Tao. Jia has blurred fiction/nonfiction lines before, and in “Caught by the Tides,” as in other long-running projects like “Boyhood,” physical changes in character become a kind of nonfiction. I’ll have more to say about “Caught by the Tides” after I’ve caught it again.

For More Movies Visit Putlocker.