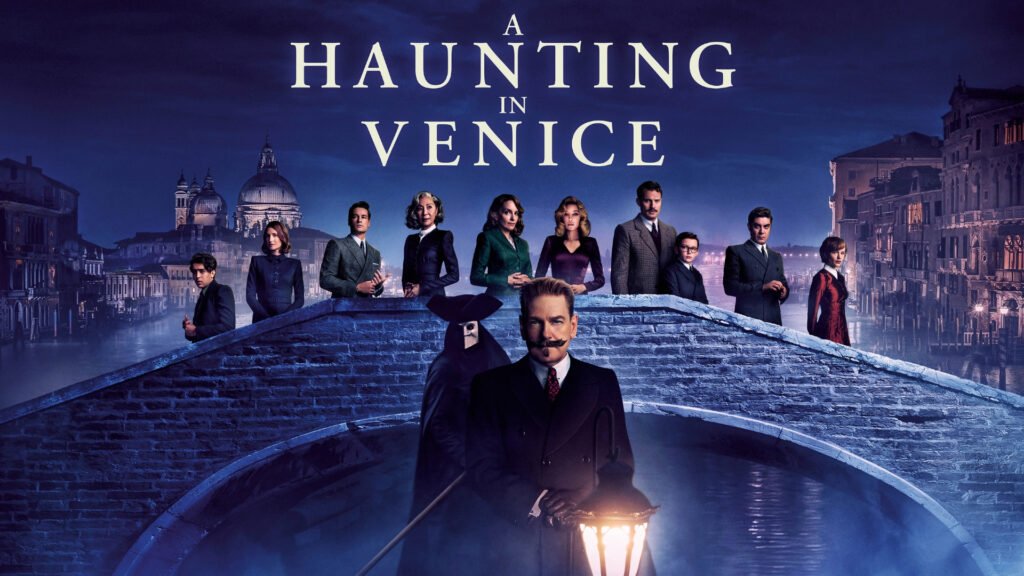

A Haunting in Venice

“A Haunting in Venice” is the top Hercule Poirot movie by Kenneth Branagh. It also ranks among one of the best films by Branagh himself because he, along with the screenwriter Michael Green, takes apart and re-imagines the source material (Agatha Christie’s Hallowe’en Party) to make a relentlessly ingenious, visually rich “old” movie that employs the latest technology.

The film is largely set within a palazzo that seems as large as Xanadu or Castle Elsinore (it’s a combination of real Venetian locations, London soundstages and digital effects), threaded with suggestions of supernatural activity; most of the action occurs during an enormous thunderstorm; and it pushes its PG-13 violence rating nearly to an R. It’s fun with a dark streak imagine a ghastly gothic cousin to Clue, or something like Branagh’s own Dead Again, which was about past lives. Also though, amid its expected twists and gruesome murders, A Haunting in Venice is an empathetic depiction of the death-haunted mindset of people from Branagh’s parents’ generation who came through World War II nursing psychic scars and wondering what had been won.

Christie published her original novel in 1969 and set it in then-present-day Woodleigh Common, England. The adaptation transplants it to Venice, sets it more than 20 years earlier than that, gives it an international cast of characters heavy on British expats working for various purposes under Rowena Drake’s roof (she gives rowing lessons) at this point in time while retaining only a few elements from Hallowe’en Party: notably the violent death of a young girl in recent memory, and the insinuating presence of an Agatha Christie like crime novelist named Ariadne Oliver (Tina Fey), who claims credit for creating Poirot’s reputation by making him a character in her books. The sales of Ariadne’s novels have slumped, so she lures Poirot out of retirement by urging him to attend a Halloween Night séance at the aforementioned home, hoping to generate material that will give her another hit. The medium is herself a celebrity: Joyce Reynolds (Michelle Yeoh), named after the untrustworthy little girl in the original Christie story who claimed to have witnessed a murder; Reynolds plans to communicate with a murder victim, Alicia Drake (Rowan Robinson), the teenage daughter of the palazzo’s owner, former opera singer Rowena Drake (Kelly Reilly), and learn who killed her.

Many others are assembled in this palazzo. All become suspects not just in Alicia’s murder, but also in the subsequent cover up killings that always follow such events. Poirot locks himself and the rest of the ensemble inside the palazzo and declares that no one can leave until he has figured things out. The array of possibles includes a wartime surgeon named Leslie Ferrier (Jamie Dornan) who suffers from severe PTSD; Ferrier’s precocious son Leopold (Jude Hill, who played young Buddy in Branagh’s Belfast), who is 12 going on 40 and asks unnerving questions about death because he saw his mother killed during an air raid; Rowena’s housekeeper Olga Seminoff (Camille Cottin), Maxime Gerard (Kyle Allen), Alicia’s former boyfriend; and Mrs. Reynolds’ assistants Desdemona and Nicholas Holland (Emma Laird and Ali Khan), war refugees who are also half-siblings

To say much about the rest of the plot would be unsporting. The book doesn’t give anything important away because even more than in Branagh’s previous Poirot films the kinship between source and adaptation is like the later James Bond films, which take a title, some character names and locations, and one or two ideas, and make everything else up. Green (who also wrote the recent “Death on the Nile,” as well as “Blade Runner 2049” and much of the series “American Gods”) is a reliably excellent screenwriter of fresh stories inspired by canonical material; his work keeps one eye on commerce and the other on art, regularly reminding nostalgia-motivated viewers in the “intellectual property” era of why they like something while introducing provocative new elements and trying out a different tone or focus than they probably expected. (The movie tie-in paperback edition of Christie’s novel has an introduction by Green that starts with him confessing to a murder of “the book you are holding.”)

So this Poirot mystery aligns itself with popular culture made in Allied countries after World War II. Classic postwar English-language movies like “The Best Years of Our Lives,” “The Third Man,” “The Fallen Idol,” mid career Welles films like “Touch of Evil” and “The Trial” (to name only a few classics that Branagh seems keenly aware of) were not only engrossing, beautifully crafted entertainments but illustrations of a pervasive collective feeling of moral exhaustion and soiled idealism the result of living through a six-year period that showcased previously unimaginable horrors Stalingrad, Normandy Beach, the mechanized extermination of human beings during Holocaust, atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And so embittered Poirot is a seeming atheist who practically sneers at speaking to dead people; Green and Branagh even give him a monologue about his disillusionment that evokes comments made about Christie near the end of her life, and in the novel, about what she perceived as increasingly cruel tendencies in humanity as whole reflected by types of crimes being committed.

With a few period-specific details and references, the source seems to exist outside of the time it was written. Branagh and Green’s movie goes in the opposite direction, It’s very much of the late 1940s. The children in this film are orphans of war and post-war occupation (soldiers fathered some of them, then went back home without taking responsibility for their actions); there’s talk of “battle fatigue,” which is what PTSD was called during World War II in previous world war they called it “shell shock”; the plot hinges on economic desperation of native citizens who used to have money, previously moneyed expatriates who are too emotionally and often financially shattered to recapture way of life they had before war, and mostly Eastern European refugees who didn’t have much to start with and do country’s grunt work; overriding sense is that some these characters would literally kill to get back to being what they were.

For obvious reasons, early in his career Branagh was compared to Orson Welles. He was a wunderkind who gained international fame in his twenties and often performed in his own projects; he had one foot on stage and the other in cinema. (He loved the classics especially Shakespeare as well popular film genres such as musicals and horror.) He had an impresario’s sense of showmanship and the ego to match it; he’s never been more brazenly Wellesian than he is here. The movie has a “big” feeling, as many of Welles’ own movies did, even when they were made for pocket change. But it’s not full of itself or pokey or wasteful: like a good Welles picture, it gets into and out of every scene as quickly as possible (the film is 107 minutes long including credits).

Film history buffs will appreciate the many visual acknowledgments of the master’s filmography, including ominous views of Venice that reference Welles’ “Othello,” and a screeching cockatoo straight outta “Citizen Kane.” At times it seems as though Branagh conducted a seance and channeled not just Welles but also other directors who worked in black and white, expressionistic, Gothic-flavored, very-Wellesian style “The Third Man” director Carol Reed; “The Manchurian Candidate”/“Seven Days in May” director John Frankenheimer. Branagh and cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos have mentioned Richard Brooks’ 1967 adaptation of “In Cold Blood” and Masaki Kobayashi’s “Kwaidan” (among others) as influences; this movie deploys fish eye lenses, dutch tilts, hilariously ominous close-ups of significant objects (including a cuckoo clock), extreme low-angles looking up at Poirot and other characters, deep-focus compositions that arrange the actors from foreground to deep background, with window and door frames, sections of furniture, sometimes actors’ bodies cutting across the shot to create additional frames with in the frame.

Like post millennial Michael Mann movies (“Collateral,” “Miami Vice”) and Steven Soderbergh’s “The Good German” and “Che” movies (“A Haunting in Venice” was shot digitally (albeit in IMAX resolution) and lets the medium be what it naturally is: a servant of light working under extremely low-light conditions. The movie doesn’t try to simulate film stock during low-light interior scenes, depriving us of that cozy “comfort food” feeling we get from seeing a movie set in the past that uses actual film or tries for a judicious “film look.” The result is unbalancing, but fascinating so; the images have an uncanny valley hyper clarity and a shimmering, sometimes otherworldly aspect (in tight close ups of actors’ faces their eyes seem to have been lit from within).

Branagh and editor Lucy Donaldson time the cuts so that the more ostentatious images (such as a rat crawling out of a stone gargoyle’s mouth) are onscreen just long enough for you to register what you’re seeing and maybe laugh at how far they were willing to go for it. Movies are rarely directed in this style anymore, nor in any format, it’s too bad, because when they are as here the effect can be heady and intoxicating.

For More Movies Visit Putlocker.