It’s an annoying fact of life in the 21st century that we rarely have enough time, or emotional white space, to sincerely care about more than one humanitarian crisis at a time. Afghanistan gave way to Ukraine which gave way to Gaza; soon enough, yet another unthinkable human catastrophe will suck dry the few minutes of each day that can be spared for international news. (We are so far behind on our atrocities coverage like, who has even thought about the Uighurs lately?) All but the saintliest among us have been guilty of prioritizing a shiny new human rights violation over an ongoing one. But then things don’t just get better once we look away. Often, they start getting worse.

It has been many years since it was trendy to talk about the Syrian refugee crisis. But this lightning-fast world has a way of creating distractions that do little to dull the harsh realities faced by millions of displaced Syrians every day. Over the past decade as a result of a brutal civil war that began in 2011 when Bashar al-Assad used chemical weapons against his own people protesting his rule more than 15 million Syrian citizens have had cause to flee their homes, many seeking asylum in Europe. Reports about refugees tend to zero in on what European countries are doing wrong while trying (and often failing) to accommodate them; for many news consumers, if not producers, stories end once someone crosses the border.

“Ghost Trail,” directed by Jonathan Millet and set along the border between France and Germany, refuses to let anyone treat Syrians’ plight as something left behind or resolved simply because they’ve found haven in a supposedly safer country. The film follows a group of middle-class Syrians who live and work in Europe by day and settle scores by night, not everyone who leaves Syria for Europe is innocent.

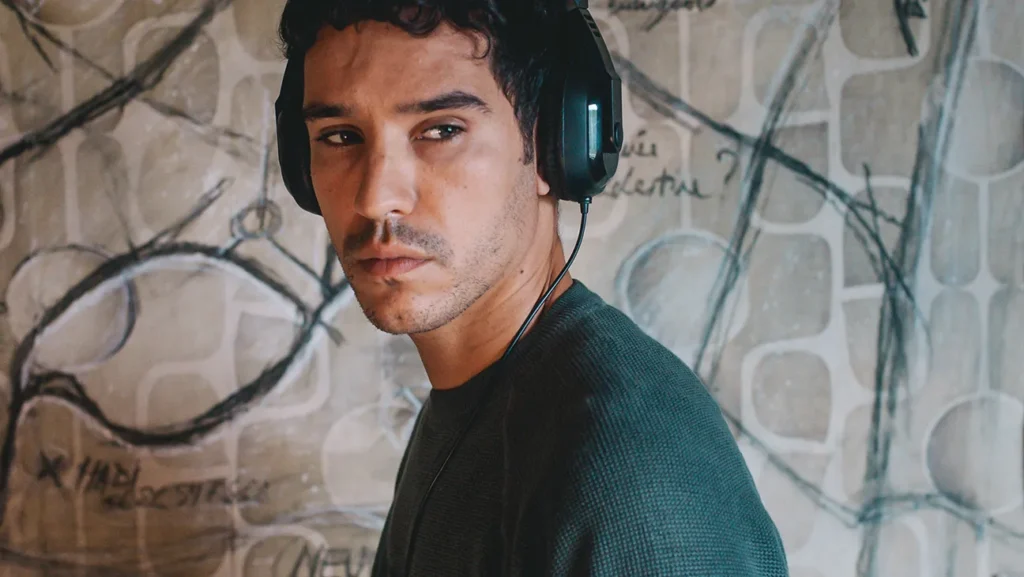

Hamid (Adam Bessa), when we meet him, doesn’t have much left through which he can remember the life he left behind. His wife and daughter were both killed in ways too savage for him to have seen or buried, since resettling himself in Strasbourg where he spends his days FaceTiming with his mother and eating at Lebanese restaurants the only thing that tells him he’s from somewhere else is that, well, he’s from somewhere else. But Hamid is not a refugee drifting through a land that doesn’t want him. He’s a man on a mission. Every night, he logs onto a server and plays a war video game with other Syrians scattered around Europe. They are an underground network united by one thing their goal to track down all of the Assad loyalists who came here having committed war crimes, so as not to face another trial, if they can help it.

Algorithms cannot flag them for these conversations because of how violently explicit the game is. So they go on these forums using multiplayer settings. There is a man Hamid knows he needs to find, Harfaz, now living in Strasbourg as Sami Hana, who tortured him and his family during the war. He thinks he’s found him and follows the man around various cafes and libraries for days from a distance.

His colleagues have an odd commitment to due process given that they’re vigilantes, they won’t let him act on his anger until they have rock-solid confirmation that this is Sami Hana. So, first things first, he has to get pictures of the guy and bring them to other Syrians who can verify before he takes him out. But every day spent stalking simultaneously brings him closer to justice and further from being able to take those healthy next steps forward.

Before making movies Millet was a stock footage photographer who traveled to Third World countries documenting war impact and poverty. The training paid off because “Ghost Trail” is rife with gorgeous shots that prove you don’t need a word to show someone’s soul so much as they hurt. Bessa plays Hamid with all the tragic emptiness of a person not allowed proper grief but forced to start anew every day in unfamiliarity; together they make some of the best spy-thriller-meets-slow-cinema I’ve seen about how wars follow us after we think we’ve gotten away from them.

If there’s one drawback it’s that Hamid’s plan is so complete and well done that you see where this movie ends rather quickly, but then again one could argue that its slow march towards an obvious destination is kind of the point. “Everyone talks about our country, the death, the problems,” Harfaz tells Hamid at one point.“You can’t start a new life if you waste your time dwelling on the past.”

He’s right, even if it hurts to agree with a war criminal; but what he fails to realize is what Millet ultimately spends his film unpacking: when everything you care about is taken from you, superficial chances at new beginnings don’t mean shit. Your inability to bury your ghosts and capitalize on those opportunities is often just another casualty of the war.

For More Movies Visit Putlocker.